Hello wonderful readers, and happy fall 🍁. If you’re anything like us, you believe that the best recipes do not arise in a vacuum, but result from hard work and creative practice, perhaps incorporating lessons from cherished family histories. Once every few months, a shallow take tends to resurface – usually via Twitter – bemoaning recipes “burdened” with “unnecessary” headnotes or essays offering “too much information” about the author’s relationship and history with a dish. “Just give me the recipe,” these (often white, male, and rarely authored-by-folks-working-in-food) op-eds demand. (See also the entitled “recipe?” comments below every creator’s heartfelt Instagram post.) Food doesn’t always have to be meaningful, but we’ve found that the most meaningful cooking often stems more than just standardized culinary directions, mixing in personal experience, anecdotes, and flair. In a direct rebuke to the “just give me the recipe” crowd, this month we’re diving into the exciting world of cookbooks, showcasing folks who’ve poured their passions and personalities into tomes we’re eager to read cover to cover.

Our interview this month features Rahanna Bisseret Martinez in conversation with Reem Assil and Illyanna Maisonet, three culinary creatives with debut cookbooks on the horizon. The Oakland native and Top Chef Junior finalist talks shop with two of Northern California’s most beloved voices in food, sharing their experiences with the pitching and writing process alongside tips for aspiring authors. We’ve also got images from Ramen Forever, a cookbook-cum-artbook curated by Yarrow Slaps celebrating this iconic dish and its creative iterations across the globe, plus an extra visual treat from artist, illustrator, and Ramen Forever contributor Maya Fuji. And as usual, we’ve got a full roundup of recs for things our communities of collaborators and friends are digging and digging into these days!

*Sometimes email providers will clip the end of our messages due to size; be sure to click through for the full issue!*

Good Soup

RAMEN FOREVER: AN ARTIST’S GUIDE TO RAMEN (2021), edited and curated by Yarrow Slaps, 304 pages, 9 x 12 inches

“As an artist/foodie I wanted to curate a book that was artistic enough to be an art book, but food orientated enough to be a cookbook. Initially, I asked artists to illustrate their favorite instant noodle creations. Additionally, they could share a recipe, a title and the price of the ingredients needed to make the dish. Once this exciting instant noodle art started to come in, I knew that I needed more. I began to think about actual ramen and started to find and interview some of today’s top ramen chefs and enthusiasts. I went down the rabbit hole of ramen. This book is a visual record of my adventures.”

More than a cookbook, RAMEN FOREVER is an illustrated love letter to this deceptively simple dish spearheaded by San Francisco-based artist and SWIM Gallery director Yarrow Slaps. Interviews with ramen heroes including Moe Kuroki, Yoshihiro Sakaguchi (Taishoken San Mateo), Hans Lienesch, Esther Choi, and Sam White (Ramen Shop Oakland) give an insider’s view into gourmet ramen spots across the global diaspora. Over 80 of the urban art scene’s most celebrated artists, including Justin Hager and Kristen Liu-Wong, contribute their own illustrated instant noodle recipes that have gotten them through struggle times. The recipes range from playful (“Hot Trash Ramen—best when you’re drunk”) to critical (“Opium War Lamian—a rustic and flavorful noodle soup enjoyed by belligerents during an unjust, cruel, and brutal colonial conflict”) to restorative (“Radiant Recovery Ramen”), showcasing the true versatility of ramen as a dish for every occasion, for people of every background and every budget. Click here to learn more about the project and purchase a copy for yourself.

Something to Chew On

Reem Assil, Illyanna Maisonet, and Rahanna Bisseret Martinez Go Beyond the Recipes

Rahanna Bisseret Martinez is a culinary creative and writer. Rahanna competed on Bravo’s Top Chef Spin-off Top Chef Junior and was a finalist. Soon after, she was invited to create menus for red carpet and special events. At the same time, Rahanna was interested in the everyday inner workings of fine dining restaurants. She has interned at Chez Panisse, Mister Jiu’s, Emeril's, Ikoyi, Californios, and other culinary institutions. Rahanna’s work appears in Teen Vogue, Food & Wine, NBA on TNT, Taste and Bryant Terry’s Black Food. Rahanna’s first cookbook, Flavorous, is expected in 2023.

Two yet to be released cookbooks reflect a love for flavor and a respect for the reader. Our two Authors are Reem Assil (Arabiyya, November 2021) and Illyanna Maisonet (Diasporican, October 2022). Reem Assil is a Palestinian-Syrian Chef and author based in Oakland, CA. She is the owner of Reem’s California, a nationally acclaimed restaurant, inspired by her passion for Arab street corner bakeries and the vibrant communities that surround them. Barely a year after opening Reem’s in 2017, Assil opened an Arab fine dining concept, Dyafa, in partnership with Alta Restaurant Group, earning a place on the Michelin Guide and Bib Gourmand’s List in its first year. Illyanna Maisonet is a first-generation Puerto Rican, cook, and author. For two years, she explored traditional and disappearing Puerto Rican recipes in a beloved SF Chronicle column called “Cocina Boricua.” Both authors celebrate the natural resources of California and their ancestral lands while inviting the cookbook reader to enjoy the universal language of great food.

Rahanna Bisseret Martinez: This year, for a variety of reasons, many more people were confronted with cooking at home. Are cookbooks more important in 2021 as a result of Covid-19?

Reem Assil: I think buying cookbooks is a timeless thing and people gravitate toward cookbooks. Some like to flip through pages and dream about being able to make the dishes without ever following the recipes; some love the stories behind food and simply read for the headnotes and narratives; and a lot of people love offering cookbooks as gifts for loved ones because they are both beautiful and functional. The years to follow will be important for cookbooks because food and stories behind them provide a window of connection to other humans. People want connection more than ever after the isolation. They want to learn about different cultures through their food ways and see themselves in those cultures.

Illyanna Maisonet: While some have said that “books are dead,” and that no one buys physical books anymore - which is why we’re seeing the demise of the brick and mortar bookstore - cookbooks will always be important. Cookbooks are pieces of art that also contain historical gastronomic importance.

RBM: What are your earliest cookbook memories?

RA: My earliest cookbook memories weren’t actually until I was 19 and living with my aunt and uncle. I stumbled on Deborah Madison’s Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone. I had just started to pick up cooking, which you wouldn’t have guessed given that I was an East Coast kid from the Arab diaspora—but I was just learning about vegetables from California. My aunt grew up on a farm and she was teaching me all about how to choose the right things from the farmers market to cook, so that book became a memory etched in my mind.

IM: I knew it was the holidays when my mom would pull out her red, spiral-bound Betty Crocker Cookbook. She’s had it forever.

RBM: You have such an interesting and wonderful style of writing. Did you have an early cookbook author, food writer or moment that inspired you to be the first Puerto Rican food columnist in the country?

IM: Puerto Rican food is my niche, I wrote something for The SF Chronicle and eventually I asked if I could be a columnist. Totally accidental that I became the first Puerto Rican food columnist in the country; I didn’t even know at first.

RBM: Did writing a cookbook change how you write recipes?

RA: Absolutely! I gravitate between two extremes — on one hand I’m a professional kitchen cook which means large scale and everything by weight after many years of training to have my own bakery, and on the other hand at home, I cook like my mama taught me — a little bit of this and a little bit of that. A cup of flour is the mug you have on hand. A teaspoon of salt is a big pinch with your hands. It was hard to adjust to a medium between those two worlds — going to precise volumes and not feeding an army. Also, how to make the directions simple enough for a home cook not having to use so many kitchen wares! Not every recipe has to be so complicated to be delicious.

IM: No. In 2018 my SF Chronicle editor gave me the style sheet from Ten Speed Press and I’ve been using it ever since.

RBM: Is there something you wish you knew before pitching or making your cookbook?

RA: It’s an iterative process! What you think the book is going to be changes a few times in the process depending on the context you are writing it in. Don’t feel the need to pack all the ideas in the pitch or even the first attempt at writing. It comes as the book evolves.

IM: You could know almost everyone in the industry, have celebrity chefs supporting you, a decent sized platform, have been a columnist at one of the nation’s largest newspapers and have paid a former editor at a major publishing house to edit your proposal, but the rules are different for you if you’re a BIPOC. So, never believe when someone says, “it’s just not marketable,” because the gatekeepers will make it harder than necessary to get a book published.

RBM: Is there someone who inspired you to create your cookbook?

RA: I wrote my cookbook with my aunt Emily, who taught me about farming and cooking. She and I were sitting one day and she was talking about how she really wanted to work on an important project. I told her that I was thinking about writing a cookbook but I was overwhelmed to do it alone after just having had a baby and opening two restaurants. It didn’t take long before I knew she was going to help me make this book happen. In many ways, she saw my evolution as a person, a social justice warrior, a baker, and a restauranteur.

RBM: Do you have a favorite recipe from your book that you cook all the time?

IM: Carne Guisada; it can be done in 30 minutes if you already have pre-prepared sofrito.

RA: Musakhan, the iconic Palestinian sumac spiced chicken dish, is my ultimate go-to. I can make it fancy by roasting the whole chicken, or make it fun like I do in my bakery, slow braising the chicken until it shreds, wrapping it in tortillas, and then cutting them up like party bites.

RBM: Many people say that the cookbook process is a marathon not a sprint. Do you have any advice for people who are pitching or in the early stages of cookbook writing?

IM: I’d love to say it’s about creating an aesthetically pleasing proposal. But, that was not my own experience. Like I said, there are two different sets of rules for two sets of people. So, the advice I would give to BIPOCs is to raise hell. You only get so many chances to pitch. If you can afford it, have your proposal looked over and edited by an editor who used to work at one of the publishing houses you want to pitch to. If you feel like you’re hitting a brick wall and you’re getting those generic responses like “it’s not marketable/there’s no market for it,” get on social media and raise hell. Your tentacles need to be in all directions because you need the support of an entire community. The more you talk about it, the more people will hear about your proposal and the more chances you have of someone coming through with helpful advice.

RA: Read a lot of cookbooks! Figure out what you are attracted to and what feels like your style. That will help you figure out how you want to tell your story (or who you want to help you write it), what kind of photographer you want, and if there is a trend in which publisher is behind the books you gravitate towards. I loved digging into cookbooks and understanding how mine would be different, or finding the elements that I loved and wanted to make sure got into my book. It really helped generate a point of view for my book.

RBM: Is there a single ingredient or cooking method that you like so much you could write a whole book about it?

RA: That’s a hard one! I love it all! I love slow braising meats in particular—is there a book about Arab barbecue yet? I’d like to conquer that.

IM: I could, but I’m not going to talk about it because it’s my next book idea.

RBM: Sometimes food writers are pushed to define something like arroz roja or sorrel while not having to define macaroons. Toni Morrison spoke about how Black writers often are forced to be an explorer or explainer. She rejected that and wrote as if she were speaking to us and in her own words said, “What I’m interested in is writing without the gaze, without the white gaze.” I feel we are approaching that in some aspects of the food world. Have you encountered this in writing your books?

IM: Not with Diasporican; my editors at Ten Speed totally understood my vision. In the beginning my editors would anglicize or italicize the Spanish words I’d use in my writing – because I love writing in Spanglish – and I didn’t do anything about it. But that quickly came to an end and I often found myself lobbying to include my own words and writing. Then it just became a deal breaker if the editor refused to include my words without an asterisk or unitalicized.

RA: Absolutely!! In Arabiyya I’m sharing the most authentic parts of myself and some honest and raw pieces of my upbringing to an audience who may have never understood the Arab experience in America. But some part of the audience may read my experience and see themselves in it, so I tried to be as honest as possible to break down some of those barriers. The reality is that my experience as an Arab woman in America who has experienced racism and patriarchy — is that it needs context. My goal was to challenge all those assumptions of me and surprise people, make them understand the intersectionality of my identity. To assert that yes, I am an Arab woman, but you cannot put me in a box.

But I’m in the genre of cookbooks and that is hard! How do you make something accessible without watering it down? I wanted to do a memoir so I kind of snuck it in between the pages of my recipes and in the recipes themselves.

RBM: Your Eater article “Don’t Call Me Chef” addressed so many problematic aspects of the food industry. One of the overarching themes to me is the importance of teamwork and respecting every team member whether the setting is fine dining, fast casual, or frozen baked products (like your frozen fatayer and par baked man’oushe); all require teamwork. In what ways is your cookbook process a team effort?

RA: Yes! I wanted to make sure that the team behind this cookbook were strong fierce women. Everyone from my recipe tester to the publishers to the photographer, stylists and illustrator are badass women. This book is as much as a celebration of their amazing work. I wanted to create a platform from them as well.

RBM: In Mexico, we didn’t have cheese or eat pigs or goats until colonization, yet there are people who consider cheesy enchiladas or tacos al pastor (which were first cooked in the 1930’s by Lebanese Mexicans) as quintessential Mexican cuisine. But sometimes the influences can be very recent – you wrote about how people “creolize” foods in your SF Chronicle article, “How Cuban Chinese refugees in Puerto Rico built a life on ice cream.” Will you speak to how this creolization is different from appropriation?

IM: I think creolization happens through necessity; an immigrant community builds their home in a foreign land and eventually the two cuisines merge. It’s not totally different from what my family had to do in California. Using aji dulces are “traditional” when making sofrito, but because we don’t have access to them here, most people will use bell peppers. Appropriation happens when some people see tacos; they see an al pastor recipe or they eat a taco. Sometimes they travel with their parents when they’re a teenager and see this taco; which can already be an issue because travel is fleeting and you’re a temporary visitor in someone else’s land. And then that person comes back to their privileged life and they feel “inspired” by the people they’re stealing the recipe from and they want to “pay homage” by creating an entire damn empire off someone else’s recipes and they never gave credit or money to that person. Or, gave money or credit to a person from that culture; they didn’t use their platform and power to uplift or help the career of someone from that culture that probably works for them, to be honest. And maybe... maybe that person even goes on a radio show and cries “reverse racism,” and asks the radio host if we’d be dragging his ass if he weren’t white. I’m starting to loop. Anyway, if the words “feel inspired by,” or “paying homage” comes out of your mouth and you’re not BIPOC. Stop. Thee end on that topic.

Enjoy a couple recipes from our contributors until their cookbooks are available to purchase:

Style Guide

Bad Chopstick Habits (2021) by Maya Fuji, acrylic & gouache on wood panel, 16 x 20 x 1.5 inches

Born in Japan and raised in the Bay Area, Maya Fuji is inspired by both her cultural heritage as well as the local microcosms of the SF Bay Area. She is fascinated by themes of traditional Japanese mythology and folklore, and blends these with her own experiences of being issei (first generation) in the United States. A recurring theme in her work is the exploration of what creates our sense of identity, and how that can shift over ones life. Soft feminine figures float through her work, encompassing abstraction, texture, vulnerability, and mystique. She layers pops of color and shape to explore themes of passing time, and to contemplate hidden meanings in the lore of her ancestors. Each piece has a story to tell — historical legends, lessons and ghost stories of the floating world era, reimagined through the lens of the digital age. Follow Maya on instagram @fuji1kenobe or catch her upcoming solo exhibition: Humid Nostalgia, opening 10/15 at Keep Contemporary in Santa Fe, NM.

“A trio of things that are either taboo or bad form to do with chopsticks in Japan 🥢

Top left: Never pass food from one chopstick to the next! The practice is called hashi-watashi (箸渡し), and is the way cremated bones of deceased are passed during Japanese funeral rituals. The word ‘hashi’ has two meanings- ‘bridge’ & ‘chopstick’ and ‘watashi’ means ‘to cross’ or ‘to pass’. The belief in Japanese Buddhism is that you cross a river in the spirit world once you’ve passed away. The ritual of passing the bones from one chopstick to another comes from this pun, inferring helping cross the bridge, or passing between chopsticks. It’s a prayer that the spirit of the deceased can reach the afterlife safely, and so it’s considered bad luck to do while eating!

Middle: This is just bad chopstick form, but I see it way too often (I used to work at a Japanese restaurant). People holding their chopsticks so low that there’s no leverage and the food gets crushed! Perfectly made sushi getting smashed into little bits.

Bottom right: Sticking chopsticks in the rice to make them stand upright. This is another reference to Japanese funeral rituals and is called makura-meshi (枕飯). We traditionally put a bowl of rice with chopsticks standing upright inside the casket during the ceremony. It is ritual to use a bowl and chopsticks that belonged to the deceased. Rice is considered a gift from the gods, and symbolizes the spirit and soul of Japanese people. The bowl of rice symbolizes a meal the spirit takes on its journey to the afterlife. Chopsticks are also believed to be holy instruments gifted from the gods. By sticking them upright, they act as a bridge to lift the spirit to the heavens. When it’s time to cremate the deceased, the rice is wrapped and placed into the casket. The bowl is broken to communicate to the spirit to move on to the afterlife and not linger in this world as a lost spirit. Again, this is considered bad form and bad luck to do while eating!”

Lunch Break

A dedicated section to boost suggestions from friends & collaborators.

Mina Stone (chef/owner Mina’s at PS1 @MoMA and author of Cooking for Artists and the just published Lemon, Love & Olive Oil): I went to Greece for the month of July. It had been three years since I had been back and during that time I opened a restaurant, had a baby, lived (am still living?!) through a pandemic (and wrote a new book!). This trip was so special and so necessary, that now that I am back in New York, I keep searching for Greece through scents or flavors. I've filled my bathrooms with Cool Soap from my favorite island of Aegina. I went to Sophia's Pantry in Boston when I visited my parents and stocked up on olive oil and mastic gum. Late night I've been watching Stanely Tucci's Made in Italy (I mean, pretty fun show!) and I recently renewed my membership with Essex Farm - the most amazing place that's growing amazing food- a revolution in and of itself.

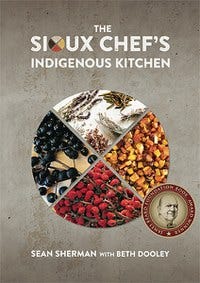

Antonia Estela Pérez (she/they; Herbalist, Educator, Community Organizer, Gardener, and founder of Herban Cura): I am currently reading Indigenous Food Sovereignty in the United States: Restoring Cultural Knowledge, Protecting Environments and Regaining Health edited by Devon A. Mihesuah and Elizabeth Hoover. I am thinking a lot about the importance of seed saving and the role that plays in preserving ancestral foods and culture. This farming season I held so many different kinds of seeds that had me dreaming of the ancestors who held the parents seeds before me. A cook book I am currently diving into is The Sioux Chef's Indigenous Kitchen by Sean Sherman with Beth Dooley. My goal for this season is to nixtamalize the maiz I grew and grind the maiz for tortillas using my metate.

Hong Thaimee (she/her, chef/owner of Pad Thaimee and Thaimee Love, and author of True Thai): I’m now in love with exploring my new business neighborhood, Greenwich Village, as I recently opened Pad Thaimee, a delivery and take-out concept inspired by my love of noodles and rice. In October, we’ll open Thaimee Love, a modern home-style Thai restaurant. I have been making new friends and feel very welcomed by my next door neighbors, Bar Moga (love their craft cocktails) and Blue Haven (so happy they are always packed)! I ate great dinners at Pinch Chinese and the all too late, great Japanese institution Tomoe. I had a refreshing and delicious spicy mango margarita at Kuxe for happy hour. I love the energy of working in this location, especially when I have an early day walking home through Washington Square Park. It always reminds me why I wanted to come to NYC and make it here!

Eric Kim (he/him; cooking columnist at The New York Times and author of Korean American): Jia Tolentino's Trick Mirror changed the way I think about the personal essay as a form for social commentary, cultural criticism and humor. Her essays have always reiterated for me that the best memoir writing subsumes the first-person writer and lets the reader take their place (or at least that's how I feel when I read her). I'm also really into Bob's Burgers right now; the later seasons are as fresh as the earlier seasons, and the writing is so sharp. I like that it's secretly a show for food lovers, too. This devastating morsel of flash fiction by Bryan Washington made me cry when I first read it on the train, so I try to recommend it when I can (unless you don't like crying in public).

Sarah Elisabeth Huggins (co-owner of Daughter): As most of us in the industry can attest, “lunch breaks” are often small reclaimed moments taken in a walk-in fridge or hovered over the kitchen sink. Truthfully, it’s been hard to find moments to explore what I'm most passionate about in food in my (lack of) spare time. Luckily, Daughter, was built to be a collaborative space, and I get to enjoy the passion and creativity of others in the little moments in between. We have the great pleasure of featuring pastries from Tyler Kenny, and to say her cinnamon rolls have become my newest obsession would be a vast understatement. Each bite is an out of body experience that fully encapsulates the feeling of home in a way I can hardly articulate. We have also had the incredible opportunity to host frequent pop-ups with friends. Recently we hosted Patikim for a Filipino BBQ and I was introduced to Ube lattes. Ube is a Filipino dessert made from mashed up purple yam and in an iced oat latte makes the perfect treat for late summer. It became an instant go-to to get me through these hectic early days.

Thanks so much for stopping by our lunch table! We’d love to know what cookbooks you’re looking forward to devouring this season. Drop the titles in the comments, or shoot us an email at hello@lunch-group.com with questions, comments, or just to say hey. We’re always on the lookout for new contributors 🔍

PS: Are we friends on Instagram yet? Follow us for even more delectable content 🍜