#2: On Borders, Boundaries, & Bon’Année

Scenes from Beirut's resilient Mar Mikhael and Chef Claudette Zepeda's Oaxacan chicken with salsa macha

Hello friends, and welcome back to Lunch Rush, highlighting some of the folks leading the charge to dream up new futures for F&B. For those of you who’ve just joined our table, we’d recommend checking out our first issue for a more robust explanation of our values.

It feels a little dishonest to open this letter with a blanket “happy new year,” particularly given the events of last Wednesday, though we do hope this message finds you as well as can be and in good health. Here are a few takes we’ve found particularly helpful for processing and contextualizing (many thanks to Susannah Blair and Lucie Steinberg for compiling). We’re also reminded of the role of corporate American food and beverage companies in coups around the world (see Dole in Hawaii, Chiquita in Colombia, and The United Fruit Company in Guatemala and Honduras). We found ourselves thinking about the concept of a new year, Gregorian or otherwise – what’s new besides a calendar date? How do we distinguish one era from the next, and what are we to make of things in between? How do we identify beginnings and ends? What makes up these borders or boundaries – are they rigid or fluid? In which cases can they be useful and in which harmful? When can crossing or bridging them prove beneficial?

This past week we’ve been thinking about how we can move forward constructively. We’re always considering the role of F&B in building community: Who are we supporting and how? What are the values these spaces uphold? At Lunch Group, we look for initiatives that cross, connect, intersect, intertwine, blur or break those boundaries to effect positive change. In many cases, this holistic approach to programming responds to conditions exacerbated by the pandemic; previously, we’ve highlighted Daughter, a cafe that has partnered with Clean Up Crown Heights, a volunteer-driven organization dedicated to keeping streets and sidewalks clean following massive cuts to the city’s sanitation department. Likewise in Los Angeles, Fifty Fifty launched Sunday Supper, a bi-weekly pay-what-you-can dinner service for anyone in need (with priority given to Black, queer and trans folks). We’re also exploring our role as residents and consumers in showing up for organizations who’ve served our neighborhoods for years. Rockaway Beach Club led the charge to diversify concessions and reinvigorate the New York boardwalk, but now requires our voices in the face of an uncertain future. In this letter, we’ll introduce some inspiring people and places from around the globe seeking to embrace and learn from difference to support and strengthen their local communities.

*Sometimes email providers will clip the end of our messages due to size; be sure to click through for the full issue!*

Aperitivo

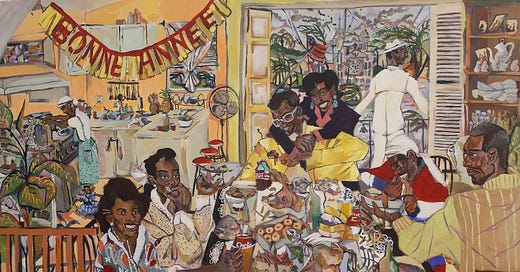

Bon’Année 1804 (2019) by Laurena Finéus, curated by Cierra Britton (she/her) for our Lunch Rush Instagram series. Cierra is the founder of Cierra Britton Art Consultancy, Senior Fellow at ARTNOIRCO, & Art Advisor at The Culture LP.

Laurena Finéus (she/her) is a Caribbean-Canadian visual artist with a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the University of Ottawa. Her approach involves a gradual layering of paint that emulates texture with an array of rippling and dense landscapes. She explores representations of Haiti and its archives, the third-space and Pan-Africanism, and is informed by her Black, female identity. Finéus’ lived experiences are centered in each of her pieces in order to create safe spaces that engage her key audience — the Haitian diaspora. Through a reconstruction of the fragmented history of the Caribbean she aims to demonstrate the complexity of its people.

Laurena Finéus est une artiste Haitiano-Canadienne spécialisée en peinture avec un Baccalauréat en arts visuels de l’Université d’Ottawa. Son approche consiste en une superposition progressive de peinture avec un ensemble de textures denses et ondulés. Elle explore dans sa pratique des représentations d'Haïti et ses archives, le tiers-espace ainsi que le panafricanisme. Ses expériences vécues en tant que femme racisé sont centrées dans chacune de ses œuvres, afin d’engager son public clé qui est la diaspora haïtienne. De plus, grâce à une reconstruction de l'histoire fragmentée des Caraïbes elle démontre la complexité de l’identité antillaise.

Something to Chew On

Natalie Robehmed & Karima Algelany on Creating Space for Culture & Community

Natalie Robehmed (she/they) is a half-Lebanese, half-English writer based in Los Angeles. She’s currently working on a podcast about capitalism and equality. In her free time, she bakes sourdough and cooks too many vegan cakes. You can follow her on Twitter @natrobe.

Karima Algelany (she/her) is the social media and logistics manager of Makan.

Makan, meaning “place” or “space” in Arabic, is a part-restaurant, part-art-gallery tucked away off the main street in Beirut’s trendy Mar Mikhael neighborhood. Formerly pay-what-you-want, the experimental eatery has played host to guest chefs cooking food from around the world since 2015. It currently serves a rotating menu of Indian, Vietnamese, and Thai cuisines through weekend buffets, set menus, and à la carte dining options. Nestled within the gorgeous 1940s Baffa House, Makan feels like the ancestral home of a chic grandparent you never got to meet, until you notice the queer and feminist art lining the walls. Makan’s combination of old and new, foreign and Lebanese, offers a delicious slice of Beirut’s thriving art scene in a city that defies neat narrativization. Located less than a mile from the site of Lebanon’s August 4th port explosion, Makan was forced to rebuild following the tragedy of government ineptitude. It turned into an ad hoc soup kitchen before reopening as the cultural space it is today.

*This interview has been edited for clarity.*

NR: What is your role at Makan?

KA: I joined Makan almost two years ago in January 2019. Interestingly, I started working at Plan Bey in [Beirut’s] Gemmayzeh as a sales person. I graduated from fine arts and wanted to do something related to publications or visual arts. I’ve done many things, but at the moment, I’m more into social media. I run Makan’s Facebook and Instagram. I also do a little bit of logistic management, sometimes service, hosting, event management... Because it’s been a tough period, generally speaking, it’s a little bit hard to define anyone’s job. We’ve been doing a little bit of everything and planning as we go.

NR: It’s definitely been an unusual year. Can you explain what Plan Bey is, what Makan is, and how those things relate to each other?

KA: We always like to describe Plan Bey as somewhere between a gallery and a publishing house. We show unique works, but we don’t sell originals. We sell high-end editions under the supervision of the artists themselves, whether it’s photography, calligraphy, illustration, or comics. As for Makan, it’s a restaurant first and foremost, but we also consider it a cultural space, introducing different cuisines to Beirut, as well as visual culture. The art on the wall, like Chaza Charafeddine with her Divine Comedy, has been a highlighted feature of Makan’s identity. It features transgender and genderfluid persons. One of them looks like [Lebanese pop star] Haifa Wehbe, I’m not sure if you know her?

NR: Of course! I have the print hanging on my wall.

KA: So you know what I’m talking about [laughs]. It’s funny seeing the different reactions of our guests. Some people recognise them immediately, and they’re like ‘Oh, why do you have Haifa Wehbe or [Lebanese singer] Elissa on the wall?’ And then we’re like, ‘No, it’s not really Haifa or Elissa.’ Near the bathroom you run into a [photo of a] topless woman [by Claudia Willmitzer] taken on the beach in Iran. The woman has her hair covering her face and her breasts. It’s a statement against certain forms of oppression against women in Iran, that also represents oppression against women in Lebanon and the Middle East. Makan used to host exhibitions by different artists. The walls keep changing, forming and reforming to accompany the cultural aspect that we consider in food.

NR: Part of what is so special is that you walk off the street and the restaurant is inside this gorgeous house. Can you tell me a little bit about it?

KA: The building itself is called Baffa House. It was built in 1945 by an Italian architect called Antonio Baffa. It’s old, but it doesn’t really resemble the classic Beirut architecture that we see mainly in Mar Mikhael and Gemmayzeh with arcades and high ceilings. It’s a little bit tucked in, which can sometimes present a challenge for guests. For the five years Makan has been open, we’ve never had a sign! And people are always like, ‘You must be new, right?’ We just don’t like to have a specific visual signifier. We use social media to advertise for Makan, but we also like word of mouth.

Sometimes, people find Makan, go in, but feel a little confused and walk out. We have to call them back in, ‘No, it’s not our house, you’re not trespassing anyone’s private property, this is what you’re looking for.’ But we like it that way. We love it to be homey and cozy. It’s not just about coming, having a bite, and leaving.

NR: It’s definitely a whole experience. It’s a bit of a secret location, sort of like a discovery – part of what feels so special. You touched on expanding food culture within Beirut. Can you give a little context for what makes Makan unique?

KA: Currently we serve Far Eastern cuisine, but in its history Makan has served cuisines from Iran, Georgia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Italy, Romania, Syria. Sometimes we ask ourselves if a model like Makan would work in different cities? The immediate answer is no. We always have to ask what defines a city, what defines the culture and the identity of a city? It’s a matter always in question. You cannot just settle with one answer. The August 4th [explosion] is a huge example. Certain events occur and you have to reshape a city and reshape the identity of a city. We think Makan is very much the offspring of Beirut.

The average Lebanese — to use simple terms, I don’t believe in “the average Lebanese” — but most of the Lebanese clientele are inclined to try the new thing in town. Beirut’s a welcoming environment in that sense. If we’re offering Vietnamese, people are intrigued, people want to try that. Beirut is [also] a central city, within the Middle East and through its connections to Europe – lots of expatriates coming in and out, Lebanese living abroad bringing their friends. We always have this dynamic motion of people. We sometimes had guest chefs from specific countries representing their own cuisine. If we throw a unique Sri Lankan night, we would have the Sri Lankan community which is huge in Beirut and Lebanon. We even had the Sri Lankan ambassador coming in proudly, like this Lebanese restaurant is representing my culture, my cuisine. And that’s quite a proud experience, I would say.

NR: What are the current cuisines rotating and what gets served when?

KA: At the moment we are serving mainly Indian, Thai, Vietnamese, Chinese, and sometimes a little bit of Indonesian or Malaysian. We keep rotating within these cuisines, mainly because these are what our current chefs are trained in. For many reasons – the pandemic, payment methods, currency devaluation, and others – it’s not as easy as before to host guest chefs.

On a Saturday and Sunday, you can come for an open buffet, which usually attracts families. The garden adds to the experience. You can have an out-of-the-city experience, yet you’re inside Mar Mikhael. Weekdays, you can order à la carte – it used to be just a set menu, but now you have the option of ordering a dish or two, which we offered for people who cannot afford or don’t feel like paying that much for a meal. For example, we have a lentil curry that comes with rice or naan – a good, healthy meal for an affordable price. But if you want to have a full Indian dinner, you can pay the price of a set menu, which we’re also trying to keep within an affordable range.

NR: Makan shifted from pay-what-you-want to fixed pricing in early 2018. Can you talk a little about that pricing model?

KA: The concept of pay-what-you-want-think-is-fair started before Makan almost seven years ago, at Mótto, our sister restaurant, or mother restaurant. Mar Mikhael wasn’t the trendy neighborhood that it is now. Motto would attract young people who were also looking to try something new. One chef who was Sri Lankan was cooking Lebanese-Sri Lankan fusions. It used to be a buffet, so people would come serve themselves and pay what they thought was fair. At that time there weren’t any other shadowing economic crises, so it was more reasonable.

NR: That’s very radical, it’s not common.

KA: Yes, I think it was also an attraction point. So it started at Motto and migrated to Makan, [where] it was a big hit. Makan means place in Arabic, or space. So the concept was to offer a space for chefs, amateur or professional, to display their talents. The chefs would pay for the ingredients; Makan would offer the space and then split profits so the chefs were more inclined to bring the best. The thinking was people would pay according to how satisfied they were. It was like a rating system in a way. Tony and other members would tell me stories about how sometimes it would put them in awkward positions with the chefs when the average per person was not that high, but most of the time it was successful. Eventually, the Ministry of Tourism asked for a fixed list of prices and it was difficult for legal and taxation purposes, so Makan had to shift to a fixed price for a set menu.

NR: You’ve mentioned it a little bit, but from my family there I’ve also heard about the currency devaluation, the pandemic, and some of the other issues that were worsened by the August explosion. How was Makan affected by that blast, and what has happened since?

KA: Even before the blast, Lebanon was going through a lot of problems and uncertainties – there was already the uprising and the revolution, plus the economic devaluation. These factors together can negatively impact a restaurant. So we would have supposedly, a full night booked and then one road somewhere would be cut, or someone somewhere will burn some tires, or the President would give a speech and then everyone is angry in the streets. All of these can be positive in the grand scheme of things, but at that moment, preparing food for 50 and then ending up serving three people… logistically, it was tricky. On the night of August 3rd we were sitting and asking ourselves, how [much worse] can it get? And August 4th proved that it can get a lot worse.

I’m sure a lot of small businesses in Lebanon have been struggling with labor. Before the economic crises, migrant workers from different countries would be inclined to come work in Lebanon because they could get paid in U.S. dollars [since the Lebanese pound is pegged to the dollar]. Since March 15th, things started changing. Business owners and employers could not pay the high salaries they could before, a problem we also faced at Makan. It’s sad to talk about it this way, employer, employee. We consider ourselves family, but money is also a big problem. They have to send money back home to their families, and when their salaries are cut down to one third, one half, it’s not fair for them. All businesses in Lebanon were, and still are, struggling with that question mark.

Focusing on August 4th, I thought this was the end of Makan. The videos and photos we saw were devastating. Everything was turned upside down, there wasn’t a piece of wood and glass that was in place. Fortunately, no one was harmed at the restaurant. We had some guests [who] were having a late lunch at the time and Hamdulillah, thank God, nobody was injured, so that’s a big positive. Still, we thought it’s game over, khalas. Or at least, this is what we thought at the time.

NR: I noticed you were serving free meals in solidarity. Can you tell me about that?

We woke up the next day and we were like, ‘We’re not going to give up. We’re going to clean up the space, fix what we can fix, say goodbye to what we cannot, but we’re all here. We’re all in good health, and maybe we have a certain responsibility.’ Because we’re in the middle of Mar Mikhael, we have this beautiful space, why don’t we just open it up? Cook meals for whoever needs or wants: volunteers who are working, cleaning up, fixing windows and people who are in the streets, neighbors. We tend to forget how Mar Mikhael is also a gentrified neighborhood. It has all the valet parking and fancy restaurants, but it also has a lot of vulnerable residents. People who have been living here for generations, some of them in very vulnerable conditions.

We had a little bit of cash left and we shopped. We bought, I don’t know how many, kilos of rice and lentils. We also have amazing chefs. They have this impulse to be giving and thankful. We almost didn’t even discuss it, it just felt so right. We sent a newsletter saying ‘if you feel like coming in to have a meal or donating, or volunteering to cook and helping us distribute meals, come.’ We were actually surprised by how it worked out from day one, it kept growing and growing.

We did this through September 4th, a month after the blast. Day one, I think we served maybe 50-70 people, mainly friends or friends of friends who were volunteering in the neighborhood, who would come eat and then leave a donation. By day 30, we were serving up to 500 people and we had a system to deliver daily warm meals to our neighbors. Over time though, we noticed that the beneficiaries, our neighbors who used to come eat, stopped coming and the beneficiaries shifted. We said ‘khalas, we have to move on.’ It was also a huge question mark, of what’s left? If we open back as a restaurant, as a business, who will come to the end of destroyed Mar Mikhael, through all the destroyed buildings and roads, to have an Indian meal?

We were too pessimistic. But we were surprised. People were very supportive when they heard that Makan was opening. Same as Kalei, Tusk bakery, and Tawlet – all those small businesses started encouraging one another. The street was reopening, and it was this, almost festive, rebirth of Mar Mikhael. People were willing to come, despite everything.

NR: I almost didn’t want to ask about the blast, because it’s so strange to be writing something for a largely American audience, where I never want people’s idea of Lebanon and of Beirut specifically to be about tragedy, or like a super clean narrative of “they’re rising above, and there’s hope.” It’s all complicated and hard. I never want to give a cliched or absolutist view. But that’s also why cultural places are important, because they offer that nuance. I understand how special and magical these nuanced places are, where there’s queer art on the walls in a really old building in an old neighborhood. It’s complicated.

KA: I think trying to explain Beirut to anyone who hasn’t visited it is an impossible task. Beirut has always had its own very unique charm. Charm is a big word, but you know what I mean—those contradictions, all built up in the same few square kilometres. The recent incidents have just intensified all of this. But it’s always been there. On almost a daily basis, we drive by the site of the explosion. I see these huge, half destroyed silos. I see this as very much representative of the self-destructive nature of Beirut, of a city of beauty and ugliness. It’s happened throughout history. Beirut will be destroyed and reborn and destroyed and reborn, and history has a lot of testimonials around that. It’s not the first time. I’m not trying to romanticize it, at least I hope I’m not.

To support Makan from afar, you can purchase prints and books from Plan Bey’s online shop (coming soon), which will ship internationally. For updates on the launch and other projects at Makan, subscribe to their newsletter and follow them on Facebook or Instagram.

(All photographs courtesy of Makan)

What’s Cooking?

Claudette Zepeda’s Salsa Macha and Oaxacan Chicken

A San Diego-based chef known for her fearless culinary style and bold approach to regional Mexican cuisine, Claudette Zepeda (she/her) is currently the executive chef at Alila Marea Beach Resort Encinitas (opening early 2021). Zepeda was named both Eater San Diego and San Diego Union Tribune’s Chef of the Year in 2018, and was a James Beard Best Chef West semifinalist in 2019. She continues to find inspiration from her frequent travels around the world and threading the quilt of human connection through food.

“This recipe is one of the oldest salsas in Mexico, having roots in prehispanic times. It has evolved with the influences of the thousands of cultures that have come through our country. There’s said to be over 200 varieties of this addictive chili oil based salsa, this one particularly is my favorite. It is influenced by enslaved Africans who taught us how to use peanuts in cooking. While peanuts were native to the region we did not consume them like they did. 2020 was definitely the year of chili oil, but for me every day is salsa macha day.” – Claudette Zepeda

SALSA MACHA

Makes 2 quarts

2 ounces chile de árbol

2 ounces pasilla or ancho chile

6 ounces garlic

½ large onion, diced

1 quart neutral oil (vegetable or grapeseed)

1 cup raw, shelled peanuts (preferably raw, Spanish red skinned)

¼ cup toasted sesame seeds

1 tablespoon sea salt

Heat oil in a large pot over medium heat. Test one chile in oil – if it bubbles and puffs it is ready. Fry all chiles, about 30 seconds each batch, taking care not to crowd the pan. Remove chiles and add to a food processor or blender. Using the same oil over medium low heat, fry onion, garlic, and peanuts individually until golden brown. Add to food processor with chiles and pulse with fry oil as needed for moisture. Add toasted sesame seeds.

OAXACAN CHICKEN

Whole roaster chicken, approximately 2 pounds

2 tablespoons salsa macha

4 tablespoons butter

2 limes, zested and juiced

1 bunch cilantro

Salt

Remove spine from the chicken, splitting the bird in two halves. Salt chicken skin liberally and set aside while you prepare salsa macha (recipe above).

Preheat oven to 400°F. Pat chicken dry with paper towels to remove moisture. Add oil to a large, oven-safe skillet over medium high heat and place chicken skin side down to sear. Place skillet in oven and roast for 20 minutes. Open oven and flip chicken skin side up, basting with salsa macha. Roast for about 25 minutes more, until the internal temperature reaches 160°F or juices run clear. Before serving, add butter and lime juice to pan, then brush chicken with butter and lime. Serve with rice and tortillas, garnished with cilantro and lime zest.

Lunch Break

A dedicated space to boost suggestions from friends and collaborators.

Jourdan Ash (Storyteller, host of Dating in NYC: The Podcast, and creating things + holding space for True to Us): I've been following (stalking) Alex and her blog Just Add Hot Sauce on IG since the first lockdown and learned a lot. My friend, Maiya Cooks, is a chef in North Carolina and just released her first line of sauces that I'm excited to try! Lastly, I've been wanting to get into fancy olive oils! I've been in a mood to infuse olive oils with some fresh herbs I have! One of my favorite (and guilt-free) things I made this year was an olive oil cake. I've been eyeing Action Bronson's olive oil but it always sells out SUPER quick!

Dana Cowin (evangelist for good food and good people, coach for creatives, former longtime Editor-in-Chief of Food & Wine, host of podcast Speaking Broadly and creator of Giving Broadly): I've fallen into various IG wormholes, finding food that makes me smile and never goes bad from yuki & daughters, and ceramics that do the same from Jennifer Fujimoto. I've been eating spicy peanut butter from Lavi created by Sergeline Malvoisin René to benefit Haiti. DeVonn Francis uses it for pad thai! I'm totally obsessed with Zabb Seasonings from Fish Cheeks and pretzels from Boy Blue Coffee. For frozen food conceived by talented chefs, check out Ipsa. For great global hard-to-find ingredients, check out Snuk. To support the New York restaurant industry, I've been cooking from a couple of books whose proceeds benefit ROAR: Family Meal and Serving New York. I’d like also to call out Jenn Louis, a chef in Portland, Oregon who’s cooking and providing basics for the unhoused in the seven tent camps.

Natalie Robehmed (writer, cofounder of FeM Synth Lab): The holiday season had me spiraling about my complicity in fancy food grift at a time when 16% of the U.S. population is experiencing food insecurity. You know, $8 sticks of Le Beurre Bordier, $20 Gjusta sandwiches across the street from an unhoused encampment and a strong sense that Something Is Amiss. To offset my food injustice footprint, I’ve been cooking for Los Angeles’ Home-y Made Meals program since listening to this episode of Theo Henderson’sWe The Unhoused podcast with Polo’s Pantry founder Melissa Acedera (support the show’s Patreon here). This year’s must read: adrienne maree brown’s We Will Not Cancel Us.

Salonee Bhaman (co-editor of Digestivo, co-leader of Asian American Feminist Collective, and doctoral candidate at Yale): As a historian, I’m often thinking about work: who does it, what it looks like, and how it’s organized (or not.) When it comes to food and wine, there’s plenty to read on the topic: I was riveted by The Cut’s feature on disgraced darling Calcarius, excited by the NYC Council adopting ‘just cause’ protections for fast food workers (more on those here) and inspired by the organizing of Los Deliveristas Unidos to demand better working conditions for delivery workers including access to bathrooms, fairer wages, and shelter from the elements. This WNYC segment from the Brian Lehrer was particularly informative.

Liz Dean (Lunch Group Collaborator): Check out this Food & Wine article on customer entitlement at restaurants.

Dana Heyward (Kitchen Lead at Daughter & Lunch Group Collaborator): Just listened to this episode of Pull It Together with Natasha Pickowicz on food and social justice; She echoes a lot of conversations that have already been happening about the industry, but I thought her talks about how her own experiences at the Matter House group were interesting.

Astrid Montaño (Encargada de contenidos en medios culturales, con 4 años de experiencia en cocinas en NY, desde lavar platos, hacer pies 🥧 y Line Cook): A Tale of Two Kitchens es un cortometraje documental que habla de los dos restaurantes de la chef Gabriela Cámara, Contramar (CDMX) y Cala (SF). En 30 minutos conocerás el día a día de sus dos cocinas, su visión comunitaria, la pasión y el amor que se aprecia en todos los proyectos que emprende. La autora mexicana nació en la ciudad norteña de Chihuahua y creció en el destino mágico de Tepoztlán, muy cercano a la Ciudad de México. Actualmente, no solo es una de las cocineras más importantes de la industria restaurantera en México, también en el 2020 estuvo entre las 100 personas más influyentes del año en la revista TIME. Es para mí un ejemplo de fuerza y talento, a principios del año pasado (antes de estos tiempos tan difíciles) tuve la oportunidad de visitar la calle de Durango, en la colonia Roma Norte y pedir un pescado a la talla (estilo Contramar, con chile rojo y perejil), increíblemente exquisito y sigue en mis pensamientos.

Mariah Barksdale (Marketer at Whiled and Pineapple Collaborative; ice cream Connoisseur): I *love* mornings, and really love easing into my day with a good article and a mug of fresh pour over coffee (I bulk buy beans from Black-owned Milk & Pull in Bedstuy). I’m obsessed with this profile of icon and pie queen Patti LaBelle, and this piece about the love of reading featuring my pal, Roxanne Fequiere (an icon in her own right). I’ve been writing down all my favorite restaurants I'd like to order from as we prep for winter hibernation — Love Nelly, Milu and brunch from Win Son Bakery are at the top of the list. I'm gifting this Grossy Pelosi shirt to myself (all proceeds go to SAGE, the country's oldest and largest national organization dedicated to improving the lives of LGBT elders) & cannot wait to stock my pantry with these adorable tinned fish from Fishwife.

Dani Dillon (Founder of Lunch Group): New year, new donabe! I have the Mushi Nabe from Natatani-en which Pineapple Collaborative turned me on to, and I've been cooking a lot of Naoko Takei Moore's recipes! I also made Maangchi's Tteokbokki recipe the other night – yum. Blown away by Café Forsaken – Raina Robinson, Leanne Tran, and Moonui Choi have an incredibly thoughtful food and beverage supply ecosystem, and bring community-focused mutual aid into practice out of Honey's in Bushwick. I have been volunteering with the Gowanus Community Fridge (part of the In Our Hearts network) – it's a very impactful leave-what-you-can, take-what-you-need model (donations go a long way; their Venmo is @thegowanusfridge and their Cashapp is $TheGowanusFridge). And I’ve been loving Apt. 2 Bread's olive focaccia and Shaquanda's Hot Pepper Sauce!

Gabi Cortez (Chief of Operations and instructor at GOOD MOVE Fitness): Having a chef for a mama and a dad who grew up learning the art of Venezuelan cooking, I sailed out of the womb with an appreciation for good food. Here are some ways I'm interacting with quality food from incredible humans these days. My chef mama founded a networking for women in food, farming and education called Women Who Inspire. Check out Marissa Lippert, founder of Nourish Baby and Nourish Kitchen and Table, who has a new project called AM//PM, limited edition provisions, baked goods & more. Taking a breath of appreciation for her quince paste and quince-coffee bean cocktail cordial. My roommates got me hooked on Too Good To Go, an app fighting food waste by offering discounted rates for surplus foods from local restaurants.

Rosa Shipley (cook + writer + wine person): I live in Hudson, where there are two beautiful community free fridges, with homes next to Kitty’s and Lil’ Deb’s Oasis. I have been really obsessed with this sage poem on sickness, by Jade Forrest Marks, who runs 69Herbs. Also, memories have been flooding back of crowded, delicious moments at Café Himalaya, which has gone through innumerable pandemic trials and needs support. And, finally, just finished Industry and took a lot of pleasure in watching Harper scarf down snacks at her little desk.

Until next month, sweet readers! Stay safe, keep cooking or crafting or planting or reading or doing whatever makes you feel good. In the meantime, follow us on Instagram for extra servings, and feel free to forward this letter to anyone you think might like a taste! And if you’re interested in getting involved, send us an email at hello@lunch-group.com.

Lunch Rush illustrations by Mahya Soltani (Graphic Designer, Co-founder of event-series Before We Were Banned, Co-Founder of Unpaid Partnerships, & Lunch Group Collaborator).