Hello sunshines 🌞 Welcome back to Lunch Rush, the official newsletter of Lunch Group, introducing you to some incredible folks reimagining equitable futures for F&B. Pull up a chair and pour yourself a cup, this month we’re talking about coffee. While many in the United States may think of their morning java routine as a personal practice to be enjoyed solo – whether that’s a bleary-eyed, rote drip operation, or one utilizing specialty paraphernalia with ritualistic precision – we’re examining the ways in which coffee is intimately bound up with community. From farming and production to cafés and coffee customs across the globe, the preparation and consumption of this everyday beverage is anything but an isolated experience.

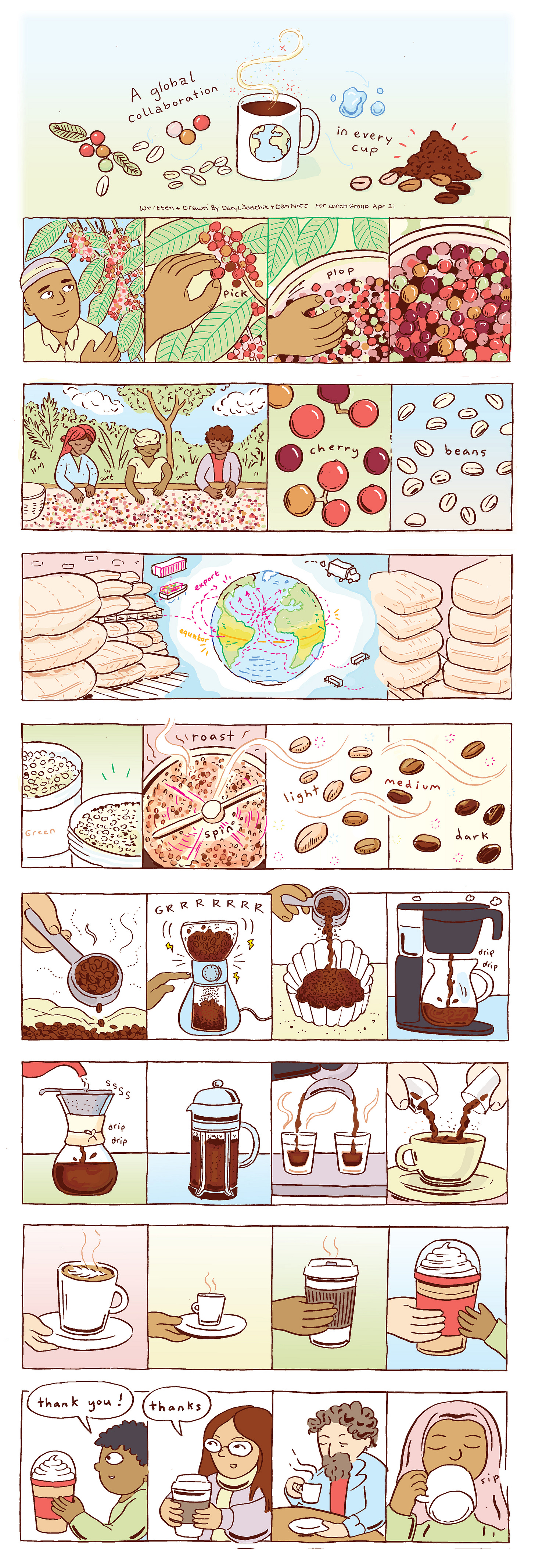

In this issue, we’ve got original images from cartoonists Daryl Seitchik and Dan Nott, a poetic sequence illustrating some of the people and processes behind your daily brew. Our interview features Sarina Prabasi – one half of the husband-wife duo behind Buunni Coffee, a small-batch Ethiopian-style roastery with locations in Upper Manhattan – in conversation with Liz Dean, a coffee connoisseur, industry veteran, and workplace equity advocate. Together they dive into the political and social dimensions of opening and operating cafés, the myopia of the mainstream American coffee industry, and visions of a more globally conscious future. We’re also sharing a recipe from Doris Hồ-Kane of Bạn Bè for Cà Phê Da Ua Đá – iced Vietnamese yogurt coffee – a drink which encapsulates the complex commodity networks foundational to both historic and modern coffee consumption.

As always, we close out with recommendations on where to turn for your next refill, how to support queer beverage establishments, roasters to watch, and more. We’re especially interested in engaging with operations steeped in community building, whether their conceptions commingled with social justice initiatives, or their rich backstories have enabled them to become bastions for communal support and healing. Read on and savor these bold suggestions for better coffee and brewing a brighter future.

*Sometimes email providers will clip the end of our messages due to size; be sure to click through for the full issue!*

First Pour

A Global Collaboration in Every Cup (2021) written & drawn by Daryl Seitchik + Dan Nott.

Daryl Seitchik is a cartoonist and teacher currently living in Vermont. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker and Resist! When she was younger, she used to pretend to like black coffee, but now she actually does. See more of her work at darylseitchik.com.

Dan Nott is a cartoonist, illustrator, teacher. He is drawing a book called Hidden Systems for Random House Graphic about infrastructure and imagination. He teaches at the Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont, and looks forward to morning coffee every night before going to bed. You see more of his art and work at dannott.com.

Something to Sip On

Sarina Prabasi & Liz Dean on Brewing Change at Buunni & Beyond

Sarina Prabasi is co-founder of Buunni Coffee with locations in Washington Heights, Inwood, and the Bronx, author of The Coffeehouse Resistance: Brewing Hope in Desperate Times, and a member of the board of directors of the Specialty Coffee Association (SCA). She was born in the Netherlands, raised in India, China, and Nepal, and spent formative years in the United States and Ethiopia. Following a career leading initiatives in global health, education, water and sanitation, Sarina moved with her husband, Elias, from Addis Ababa to New York City, where they started Buunni Coffee together. On Twitter, she’s @SPrabasi.

Liz Dean is a lifelong enthusiast of all things food & beverage and a Lunch Group Collaborator. She worked for eight years in the coffee industry, starting as a barista and eventually working her way up to become Director of Retail for a small chain of coffee shops in New York City. She’s previously served on the Barista Guild of America’s Executive Council, as well as the SCA’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Task Force. She now works in what arguably is still part of the F&B industry (for our canine friends) as Director of Customer Care for a subscription-based dog food company. Liz has strong feelings about leadership in the workplace and is deeply passionate about developing and empowering the teams she works with through trust and respect.

L: One of my favorite questions to ask when hiring people for cafés: what is your favorite coffee memory?

S: I grew up in a tea drinking culture, so my early experience was Nescafé with lots of milk and sugar. I discovered good coffee when I visited Ethiopia. A friend and mentor took me to this coffee shop. It was like entering a different world. I can still picture the sunlight coming through the windows. The smell of coffee just washed over me. You had to buy color-coded tokens from the cashier. Liz told me to order a macchiato – I think a green token. There were these older gentlemen in uniforms preparing the drinks. No words were exchanged. I gave my token and got my drink. Right after drinking it at the counter, I said, ‘Liz, I need another!’

An Ethiopian-style macchiato - still my favorite drink - is different from the classic Italian version. The milk is steamed with a tiny amount of sugar, which creates these layers - the milk and espresso stay separate.

L: I’m curious to know some of the differences between Ethiopian and American coffee culture.

S: People often talk about the Ethiopian coffee ceremony, which is important. But there’s also a thriving urban coffee culture in Ethiopia, hanging out in cafés, drinking macchiatos or espressos. Or the coffee ceremony as it’s adapted to more modern lifestyles, a weekend thing to relax with family and friends. In more rural areas, there’s more traditional coffee-making happening.

In the U.S. we take coffee to go, in Ethiopia we have coffee to stay. And I mean, to stay, and stay, and stay - like for three hours. In America, it’s often utilitarian: “I need my coffee to wake up.” There, it’s “let’s get together, it’s been too long since we had a chat.”

Coffee in Ethiopia forms the livelihood for so many people. There’s a whole economy around coffee, from farmers to traders to buyers to exporters – even the government is interested. Because of colonialism, coffee was introduced as a commodity or export crop in many parts of the world. That’s true in Ethiopia now, but historically coffee was something you picked in your backyard.

L: Tell me about how Buunni got started.

S: I lived in Ethiopia for eight years while working in the international NGO space. It’s where Elias and I met and married. When we moved from Addis to NYC, I was going to look for a job, but Elias had been a serial small-business entrepreneur. When you hear about Ethiopia in the west, people think of drought and famine. He wanted to work on something that would highlight a positive view of Ethiopia, and Ethiopians are very proud of their coffee.

We were just going to do wholesale. We went to local events and did tastings. Everyone asked if we would open a coffee shop, but that wasn’t the original plan. One day, we saw a “For Rent” sign in this tiny old shoe repair shop around the corner from us. We told ourselves, we’re just looking. It was in terrible shape, but it had potential. We said, let’s try. I submitted the most comprehensive business application. I reached out to neighborhood parents and printed responses to attach to our application. Elias had plenty of experience in Ethiopia, but in the U.S., your experience elsewhere doesn’t count. We got letters of reference from anyone we knew. The landlord wanted to meet at this deli in midtown. He said, “My wife says we should give you the space. She liked your application.” We were thrilled.

L: My parents moved to this neighborhood a decade ago. Most people I know have never been here. They’ve maybe been to the Cloisters, but not this particular area. The first time I went to Buunni, I thought, this is the type of charming coffee shop you’d find in a small town - it’s really part of the fabric of the neighborhood.

S: In retrospect, we were lucky. Elias was confident. He’s good with numbers, but besides that, we didn’t know anything – where to get milk, or any of the basic things to run a business here. Elias did a coffee course. We went to every coffee event we could. All the grassroots things we did meant talking to people all the time. Elias left his social life in Ethiopia, so this was a way to get to know people in a city where you can be so anonymous. Starting a business so reliant on relationships meant that pre-pandemic, people often recognized us. On the subway once, this kid yelled, “Mr. Buunni!”

L: You’ve found so many ways to imbue the community in the café. I’m curious to hear more about your philosophy.

S: It was about getting to know our community, but also contributing something to this home we were making for ourselves. Especially pre-pandemic, there was a lot of activism at our cafés, oftentimes guided by our customers.

We had decisions to make: What is our place as a business in the neighborhood? How should we be showing up? As an immigrant business and as a Black and Brown-owned business, we had our opinions. But the activism has been organic. So much of our identity was being a gathering place. We had performances, readings, community events. The schedule last February was full. It felt like a natural evolution.

In Ethiopia, it’s always “Let’s have coffee.” It’s a group activity. That’s how we approached Buunni. I love when people say “that’s our coffee shop.”

L: I miss that. My customers would bring in their friends and say, “Oh this is my coffee shop. They know who I am.”

S: That sense of [communal] ownership, that makes me proud.

L: But there’s a challenging line you walk as a business owner. Have you had to deal with negative reactions to social justice stances you’ve taken?

S: I’ve steeled myself for backlash. So far, we’ve been lucky. If people aren’t happy, it’s not been blatant or direct. There’s definitely subtext on some Yelp reviews, but part of it is the neighborhoods we’re in. Pre-pandemic, only a tiny portion of our business was online. People following us had directly engaged with Buunni. But this year, our online presence has grown, bringing people who haven’t followed our journey. We’ll see what trajectory that follows. I wrote about the white supremacist rally in Fort Tryon Park in Coffeehouse Resistance.

L: Yes, I remember that!

S: There was a lot of shock. Those moments felt like warning signals. But we’ve had a buffer of amazing, vocal community support.

L: It’s that communal pride - the coffee shop is everyone’s.

S: Still, I worried about my book. I was very direct about my beliefs and experiences. I started writing right after the 2016 election – initially, to process. You could look at it like a memoir, a story of a specific stage of life: our life in Ethiopia, moving to the U.S., starting a business and family life. But you could read it as a coffee story, this idealized vision of place, this immigrant American dream. At the time I wrote it, it felt important to not skirt around what was going on. Just having moved to this country deliberately – not running away from something, not from war, not as refugees, but just as people in the middle of their lives and careers, deciding to raise our children here, and questioning that.

L: I remember getting into arguments with coffee people outside my bubble. We’d talk about inequity within the industry and inevitably someone would say, “Stop making it political, we’re here to talk about coffee.” But coffee is political. If you know anything about its history, about colonialism - you can’t separate them. It’s really messy. I’m of the mindset that we should lean into it.

S: In that sense, it’s a messy book. You write from the perspective of where you are at the time. The book I’d write today would be different.

L: How have you had to adapt your business to survive the past year?

S: In the beginning, we shut down. It didn’t seem right to stay open. When we did re-open, we signed up with this mobile order platform. Pre-pandemic I wouldn’t have wanted that, but I laugh because now it’s become really important for many of our customers who otherwise wouldn’t feel safe.

We did our best to communicate with and reassure our staff, but there was just no guidance. We were all on our own. Okay, businesses are supposed to close. But then what? What does that mean for the people you’re responsible for, how do you pay them? That feeling of not wanting to abandon the people who’ve helped grow your business... I worked in international public health, so I felt very ready to make decisions that needed to be made, but there was just no information, no support. We did the best that we could. We didn’t have to lay anyone off, but we had a lot of people who had to leave New York. We tried to be supportive, but didn’t feel like we had the resources.The media wrote about people who chose to leave, saying, ‘I’ll just buy a house somewhere so I can wait out the pandemic with a yard.’ Those stories were so far from their realities.

While we were closed, we made coffee for frontline essential workers. It was such a tiny gesture. But it felt like something we could do. I think our customers were also feeling very helpless. So it also felt like something that they could do.

L: That was me! I thought, “I can send coffee to essential workers!”

S: Yes! We were all sitting at home, listening to the sirens. It’s hard to think about now. We just kept brewing. Elias did deliveries. It helped keep us going.

Then we were able to re-open, carefully, week by week. We started doing Ethiopian food in September. One of our staff is Ethiopian and a great home cook – we were able to bring her on full-time and another person part-time.

We’ve been doing virtual coffee tastings. We try to make them interactive because everyone’s tired of Zoom. It’s nice to talk to our customers in a way we haven’t been able to.

L: It’s hard to imagine a post-COVID world, but I feel like I can finally allow myself a tiny bit of hope. What do you imagine the future holds for Buunni?

S: It’s hard to put into words, you don’t want to jinx it! But I think, in some ways, we’ll emerge stronger. But different. We can start to be a physical place again, outdoors at least. Some things - the virtual tastings - will continue. We’re still figuring out what type of business we want to be moving forward, what we don’t want to bring back.

As horrible as the pandemic was - there was also a shakeup, an opportunity for bigger systemic changes. But, that didn’t happen over the past year. I’m curious about the longer term; how will we behave differently as individuals, as political leaders, businesses?

L: It felt like there was a reckoning companies began to experience - as, understandably, employees past and present, began saying, “Hey, wait a second, you’re posting these black squares, but you treated me or my co-workers terribly.” It felt like something was going to change. But it’s hard when there are other forces keeping people pinned down. I don’t feel like we did what we could’ve done.

S: With change, you don’t really know when it starts or takes hold. Something that really struck me during the pandemic was all these regulations and sudden changes. Elias and I have said so many times, just because we can, doesn’t mean we should. It came into stark relief during the pandemic. It doesn’t matter if we’re allowed. What feels like the right thing to do? It’s good to keep reminding ourselves as things are getting back to “normal”.

L: Outside of the pandemic, what do you see as some of the industry's biggest challenges?

S: I think climate change is the biggest challenge, in all industries. Inequity within the coffee industry isn’t sustainable. There’s a lot of dynamism in terms of changing these colonial hangover structures. But we’re at the tip of the iceberg. We haven't acknowledged or acted on all of the problems within the industry, in the U.S., or globally.

L: What other coffee companies are you a fan of?

S: I really admire Kahawa 1893. She’s a 3rd generation coffee farmer based in the Bay Area. She was mainly supplying coffee to offices, but now does direct-to-consumer coffee with a tipping mechanism that goes directly to farmers. I also just read about a mother-daughter coffee shop [called Bean & Bean] in Boss Barista. I’m interested in anything people are doing a bit differently - the story is as important as the coffee.

L: I love that. I went through a period when I was a coffee snob, but now I’m more interested in supporting companies doing interesting things.

I worked in coffee because I loved taking care of people. I worked at a tiny spot called The Monkey Cup in West Harlem. Their set up was very DIY, and their coffee was good but it wasn’t the most important thing. Pre-pandemic there was so much focus on hyper-premium products and spaces, oftentimes opening in neighborhoods without thinking about how business will impact residents. The owners are Venezuelan, and very welcoming to Spanish speakers. Anyone was welcome to come get coffee without navigating some complicated menu.

S: There’s an art and a science to coffee. I’m more interested in the art. I’m a big believer in science, but sometimes it’s part of the post-colonial legacy. Who decides what coffee is good or the “right” way to make it? Part of me just doesn’t like this hierarchy of knowledge. Valuing a certain type of coffee science ends up financially benefiting a certain type of people, and that’s not by accident. I really respect and value the multitudes of ways that people have been preparing coffee for generations. We’re technically specialty coffee but we also have to get over ourselves.

L: At cuppings, there were always guys naming all these fruits no one had heard of. It drove me crazy. Some of my staff would say, ‘I don’t know what that is.’ And I’d say, ‘That’s their perception, but your taste is your taste.’ I liked to invoke memories – like a warm day having a picnic in the park, rather than specific flavor notes. Taste and memory are so closely tied. For me, that’s much more accessible. And lots of fruits they were naming are tied to colonialism. The reason they even know what they are is because someone brought them here.

S: Or people from other countries have never tasted them. Blueberries aren’t common in parts of the world. Or roasted pecans! It’s culturally specific. Ethiopian coffee is not always the most accessible. It’s not what a lot of Americans grow up thinking coffee tastes like. I think a lot of the American coffee industry is very self-serving.

L: Natural-processed Ethiopian coffee made me realize that processing and origin can impact taste. Because of the gatekeeping in the industry, so many people might be denied this opportunity or looked down upon for having this moment of revelation that everyone should have. It’s fun to discover that.

S: I’d like to see how we can expand cuppings at Buunni.

L: I’m excited for when things get normal-ish. I’d love to participate.

What’s Brewing?

Doris Hồ-Kane’s Cà Phê Da Ua Đá (Iced Vietnamese Yogurt Coffee)

Doris Hồ-Kane is a proud daughter of refugees; boat people. She was born in Texas but considers herself a New Yorker, having lived in the city for 20 years. She is the owner and baker behind Bạn Bè, NYC’s first Vietnamese American bakery, as well as a historian, archivist, and the founder of 17.21 WOMEN, an online archive of Asian Pacific Islander trailblazers whose legacies have been buried by hegemonic historical narratives. A forthcoming book of her research will be published by Penguin Books. Prior to her current projects, she spent over a decade in the fashion industry as an apparel designer, buyer, creative consultant, and stylist. Doris currently lives in Brooklyn with her husband and three kids.

*Photos courtesy of Doris Hồ-Kane*

“With the bakery/café opening soonish, I’m often asked, ‘What makes coffee Vietnamese?’ Some say it’s the way it’s brewed (with a phin filter), others say it’s the bean itself – that it should originate from the motherland. As long as you use a deeper, dark roast, you can get good results, but I love using Nguyen Coffee Supply’s robusta beans. They’re invincibly strong and straight from the source. My recipe is for cà phê sữa đá (iced milk coffee) with a full fat, creamy twist. I’ll usually make my own da ua (Vietnamese yogurt), but plain Greek yogurt with sweetened condensed milk can work in a pinch. Yogurt was introduced to Vietnam through French colonization. Scarcity is the mother of innovation, and because fresh milk was a scarce luxury in tropical weather, especially during the late 19th century, condensed milk was and still is the base for a lot of Việt recipes that require dairy, like yogurt. I love this variation of cà phê sữa đá because it’s so rich and tangy. I’m also just a huge fan of dessert-like beverages.” – Doris Hồ-Kane

Cà Phê Da Ua Đá – Iced Vietnamese Yogurt Coffee

*I grew up calling it Da Ua which comes from the French word for yogurt (yaourt), but it is also referred to as sữa chua.*

Serves 1

INGREDIENTS:

2 tablespoons Nguyen Coffee Supply TrueGrit beans

¼ cup and 1 tablespoon boiling water

½ cup whole milk plain Greek yogurt

2 tablespoons sweetened condensed milk (I prefer Longevity Brand but any brand will work)

2 tablespoons whole milk or any plant-based milk (oat milk works best)

Ice

INSTRUCTIONS:

Before starting, place a 12 ounce glass in the freezer. This will help keep the ice and yogurt from melting and further diluting the coffee too quickly. Another way to avoid this is to let the coffee cool to room temperature. Do both for maximum cà phê chill.

To prepare the coffee, you’ll need a phin. Add the coffee grounds to the main brewing chamber and tamp it down with the perforated press. Place the plate and chamber on top of a short glass or mug. Add 1 tablespoon of hot water and let the grounds bloom for 20 to 30 seconds. Then, add the remaining water to the chamber and cover with the cap. It should take about 5 minutes before the last drip.

While you’re waiting for the coffee to drip, mix the yogurt, condensed milk, and milk together to fully combine.

Remove glass from the freezer and fill ⅓ with ice. Add yogurt mixture, then pour coffee over that. Fold everything together. You can eat it with a spoon or slurp it with a straw.

*Optional but highly recommended: top with a light drizzle of condensed milk, a dash of Sài Gòn cinnamon, and the tiniest bit of Maldon sea salt.*

Coffee Break

A dedicated section for suggestions and recommendations from friends and collaborators.

Cydni Patterson (she/her, head tea spiller at Cascara): One of the things I have missed about enjoying coffee inside of my local shops is the plant life! I signed up for a monthly succulent subscription with Succulent Studios. Those little babies bring me so much joy. I have been obsessed with making two drinks: a shot of Little Waves Coffee with my Flair, or cold brew cut with toasted coconut water. If I’m staying home, my favorite mug is the Origami Sensory Cup from Slow Pour Supply. If I’m on the go, I’ve got to have my coffee in my Fellow Carter Move Mug with Lion Babe in my ears. The vibes are always great and the coffee stays safe and warm!

Ashley Rodriguez (she/her; freelance writer and creator of the Boss Barista podcast and newsletter): I've been thinking a lot about podcast interviewing lately—I told a friend that audio is the most visual form of storytelling, and I learned that from Jessica Abel's Out on the Wire, a long-form comic book on telling audio tales that I come back to constantly. I recently celebrated my birthday with takeout from Tacos Lotería (we almost ordered back-to-back meals because their food is so good) and a custom cake from Butterbird Bakery, inspired by my grandmother's proclivity to put out graham crackers, cream cheese, and guava paste at the end of a meal and call it dessert. Today in my cup I'm sipping a coffee from the Café Brisa Serena co-op in Timor-Leste roasted by New Math Coffee, a roaster highlighting specialty Asian coffees.

Alexandra Lisbeth Zepeda (she/her, Bronx based Queer Latinx Coffee Professional, Creator of Caffeinated & Melanated): Personally, it is most pleasing to see womxn dominate what are typically considered male roles in the coffee. This is especially true if we look at what I think is the backbone of the industry: farms. I’m excited by producers changing the game like Rosalba Cifuentes of Mayan Harvest Coffee in Mexico and Karla Boza of Finca San Antonio Amatepec in El Salvador that focus on womxn lead sustainable farm initiatives. Curious to try their coffee? Keep an eye out for US-based Latina roasters like Little Waves or Mother Tongue for their product!

Erica Rose (she/her, film director): A place at the table has taken on a deeper, more challenging meaning as we’ve faced the biggest public health crisis of our lifetime. Food does not have a sexuality, but that does not exclude it from being queer. I recently co-directed a short documentary that showcases the movement of Queer Food and how it nourishes, feeds, and cultivates the LGBTQIA+ community. We explore this concept through chef Kia Damon's personal story, her gumbo, her chosen family, and the Kia Feeds the People mission: feeding her Black & Brown Brooklyn community and providing access to delicious food. Donate today! I’m also loving Ursula’s weekly Queer Pop-Up Series. We have to show up for our queer spaces - something near and dear to me that you can see in my work, most notably with The Lesbian Bar Project.

Thanks for reading, friends! Don’t forget to follow us on Instagram for more fresh F&B content. And if you’ve got a project you think we should know about, a question, a comment, or just wanna chat, send us a message at hello@lunch-group.com!